Welcome to k!3

Welcome to k!3,

where Kenyan writer Richard K responds to his experience of an IDP camp in Gulu, Uganda, in prose and poetry, and Louisa M.J. in Wales responds to his words using digital and acrylic media . Coming up in the next issue : Traditional artist Sanaa Gateja paints on barkcloth, his pupil Kateeba Anthony prefers a more modern approach - kushinda! explores their techniques, motives and inspirations. Past Issues : k!2 Matt Bish on Ugandan films k!1 music, art, theatre

GULU - A CROSS CULTURAL REFERENCE

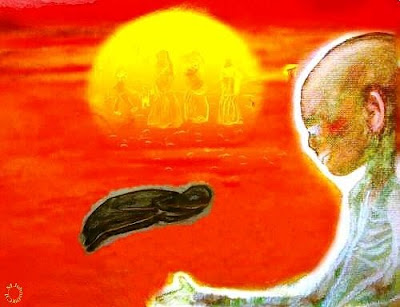

The Children of the Camps and the Angels of Mercy

by Richard K

The bright sun moves down the cloudless sky yet another day

Over the desperate eye of an expecting soul,

Its ominous heat burning the earth to red ash

And the whirls gathering the ash into dust.

The wind has not won the fight

To drive the red dust away,

Neither has the rain come trickling down

To cool the boiling souls to hope.

The expecting eye wanders away

To seek the face of an approaching visitor,

The heart runs but the lips remain tight.

And oh, the silence!

The hardly covered bodies,

Their beginning-to-bulge bellies,

The scarcely-haired scalps,

The parentless kids,

The kidless parents,

The innumerable beads of mud shacks,

The numerable grains on infected floors,

The spectacle of searing hope under the Gulu sun!

Is it not a sad story?

The children are sick of the disdain,

The children wish to laugh again

And play and run home to warmth again,

But who has called their mercies forth,

And shaken their hands free,

To cradle the children to their breast

When they come running to them?

We are clamped up in an old van, about nineteen of us including the driver. The journey to the camps seems endless. I cannot estimate how long it took us to arrive there for I had completely lost the sense of time on arriving in Gulu. Keeping a watchless wrist to me is a habit that dies hard since I sometime fail to see the logic of dividing up the river of time or attaching numbers to it. However, the about thirteen kilometres road down to the nearest camp is rough and dusty, and seems to start right where the tarmac connecting it to Gulu town ends. One has to climb down a small depression that stands as a mystical demarcation between rustic and urban, galore and dearth, hope and despair. I deeply sympathise with those that have taken the road to the camps without the hope of return. The van move s at a very slow speed on taking the dusty road as if afraid of venturing further down and, led by Dennis Kimambo in the words of some Alma mater lyrics that he sung to his high school bus driver, and in chanting some Kenyan matatu, hyped up whimsical we encourage the driver to keep pressing the accelerator ever harder. I am sandwiched between two beautiful Ugandan ladies and listening to one Joanita Nambi on my right who relates to me the challenges she is encountering trying to sell the ABC ideals of Roll Back AIDS , but I am not fated to concentrate entirely since the van keeps sucking in dust that has now almost suffocated us. The creaking sound of the old loose metalwork scares me and I am afraid that the chassis will give in under the pressure of our load as the van keeps coming down hard upon the bumpy road. My fears are almost consummated when Christina's car, in the dexterous hands of our friend George, fires fast past us leaving behind it a monstrous cloud of red dust that swallows us, obscuring almost everything, but luckily the van does not veer off to hell as I was fearing.

s at a very slow speed on taking the dusty road as if afraid of venturing further down and, led by Dennis Kimambo in the words of some Alma mater lyrics that he sung to his high school bus driver, and in chanting some Kenyan matatu, hyped up whimsical we encourage the driver to keep pressing the accelerator ever harder. I am sandwiched between two beautiful Ugandan ladies and listening to one Joanita Nambi on my right who relates to me the challenges she is encountering trying to sell the ABC ideals of Roll Back AIDS , but I am not fated to concentrate entirely since the van keeps sucking in dust that has now almost suffocated us. The creaking sound of the old loose metalwork scares me and I am afraid that the chassis will give in under the pressure of our load as the van keeps coming down hard upon the bumpy road. My fears are almost consummated when Christina's car, in the dexterous hands of our friend George, fires fast past us leaving behind it a monstrous cloud of red dust that swallows us, obscuring almost everything, but luckily the van does not veer off to hell as I was fearing.

There are three modern buildings on the one side of the narrow pathway that deviates a short distance off the main road into the camp. One of the buildings is a pavilion with the resemblance of a mystical shrine while the other two hold the offices for charity and other welfare servic es. In one of the rooms an adult education class is in progress and I am worried lest we be mistaken for tormentors when we rush in interrupting, but George, swiftly as always, intercedes for the entire group in a translated explanation not only of who we are but our mission here as well. Outside a group of half-naked children - most of whom bear two shiny stripes stretching between nose and mouth, a trademark of an ailing infant population – mills around the building like disheveled scavengers milling around a feasting pride of wild cats. I want to sit for a photo with them but when I beckon to them to congregate some tall boys, (from whence they appear is a puzzle to me), with forbidding countenances warn them against what I conjecture as mixing with or bothering the visitors. Nevertheless I remain adamant until at last the children submit to my persuasion and Paul, Madi and I in turns seat ourselves for photos with the children, who cling to our trousers like they shall never let go. The children's eyes remain glued to the empty mineral water bottle that I am holding, luckily I manage to quickly dispose of it without their noticing.

es. In one of the rooms an adult education class is in progress and I am worried lest we be mistaken for tormentors when we rush in interrupting, but George, swiftly as always, intercedes for the entire group in a translated explanation not only of who we are but our mission here as well. Outside a group of half-naked children - most of whom bear two shiny stripes stretching between nose and mouth, a trademark of an ailing infant population – mills around the building like disheveled scavengers milling around a feasting pride of wild cats. I want to sit for a photo with them but when I beckon to them to congregate some tall boys, (from whence they appear is a puzzle to me), with forbidding countenances warn them against what I conjecture as mixing with or bothering the visitors. Nevertheless I remain adamant until at last the children submit to my persuasion and Paul, Madi and I in turns seat ourselves for photos with the children, who cling to our trousers like they shall never let go. The children's eyes remain glued to the empty mineral water bottle that I am holding, luckily I manage to quickly dispose of it without their noticing.

Across the other side of the pathway, when we turn to look, the actual camp stands - a regrettable vista of a multitude of tiny thatch and mud huts that seems to extend ad infinitum . Charity and I are in front leading the group into the camp but we are halted to give room for George's vanguard. Meanwhile, Charity and I challenge each other to discover the purpose of an unroofed hut, much smaller than the rest, that stands on the camp threshold like a ghost some ten metres or so away from the next hut. I am utterly disturbed on tugging at the gaping door, not by the appalling stench that suddenly screams into my nostrils but by the mound that has formed through accumulation of continual defecations and the some-inches-deep footprints upon it that make it look like a large ghostly face, mockingly staring,that seems to have stifled the stench until the moment we peer through the door. The other huts are about the size of a soccer pitch center circle or smaller and each is just a few centimetres away from the other as if one would not stand up alone . There is however enough room for paths about the camp but the striking closeness of the huts has a rather profound meaning: the extent to which the magnetism of common social predicament has pulled the compact of the people of the camps tightly together. As we walk about the camp I note that much of it is deserted save for a few people, most of whom are old folks. These, like the children, are poorly dressed and look rather emaciated. One cannot help but notice their scantiness accentuated by the amount of grains (enough to feed a single hen for two days), predominantly maize and sorghum, drying on the floors. Outside another hut I notice a heap of cones of some local fruit (is it wild or not?) but I do not comprehend whence the cones come or what they are for until we nearby encounter some men - I am not sure if youthful or otherwise - who are gradually soaking in some intoxicating local flavour and when those behind us salute them the men mockingly intonate in some bad Kiswahili.

It does not takes us long to emerge on the other side of the camp where we find the shopping centre comprised of, as the rest of the camp, fabricated buildings of mud. The children, those who attend, are returning home from school and Njoki and Brenda lead the rest of the group in singing some songs. Sweets are bought for the children and some kind words are exchanged. I am finding the urge to have another puff irresistible and so I cross to the other side of the road, lest I set the grass thatched camp ablaze,to light my cigarette . Thinking about accidental fire attracts me to the consideration that I can almost hear the scarcely green grass cracking under the immense heat. I also re-examine my need to smoke while those children have hardly enough for dinner, but I succeed in consoling myself that it makes little difference if I, after all, puff out my stick now or not.

Much calmer than when we came we ride back in almost muted silence. I go straight to the lady who had fueled the desire to visit the camps and I find courage to express my most sincere gratitude to Christina and the LiA Centre on the one hand and the Charity for Peace on the other for the wonderful work they have done, and continue to do, for the children and the impoverished people. It is my hope that many more people will be touched by the spectacle of wretchedness evident in the camps and will be inspired to do something to improve lives there.

Words : Richard K, Kenya

Pictures : Digital and acrylic montages by Louisa M.J, Wales